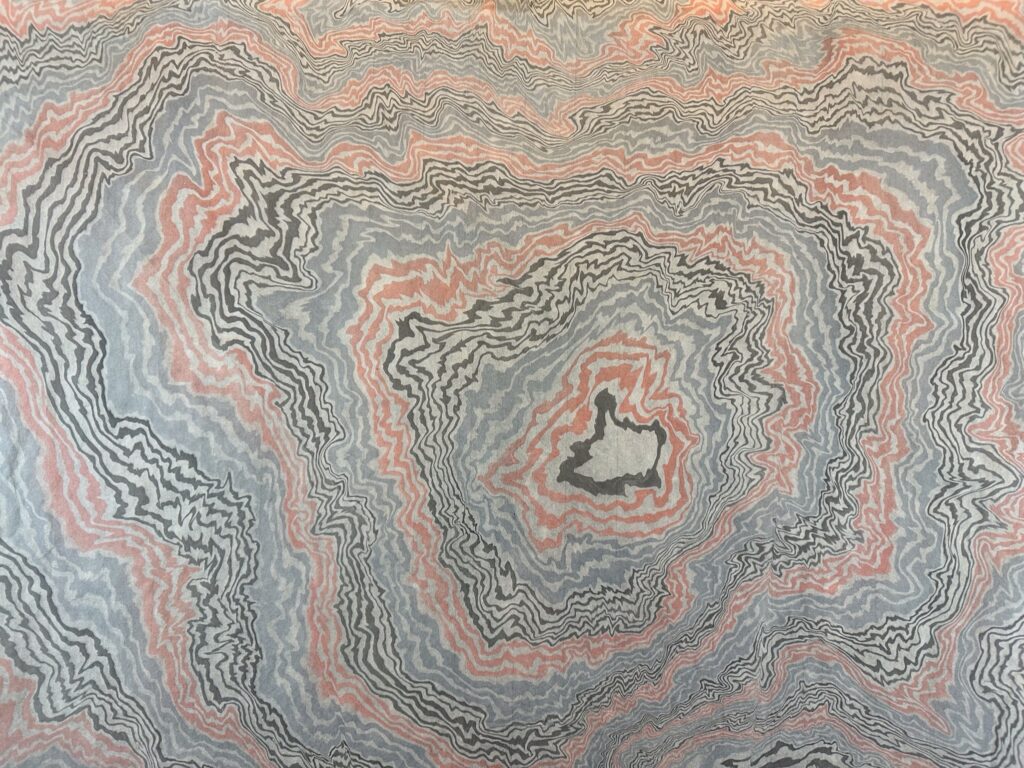

I use this term to describe what is commonly taught or found in online video demonstrations. With this style, rings of ink (one or more colors) are alternated with the dispersant and the process continues until the entire tray is filled. Various techniques are used to shift or alter the pattern, such as fanning, blowing, drawing through the rings with a stylus or fine wire, and then the paper is laid down to capture the image. Stylistically, this pattern is a late development in the history of suminagashi – colors other than the traditional sumi began to appear during the late Edo period (18th and 19th centuries), as do examples of full coverage of the paper. It may be that, as Japan modernized, particularly in the 19th century, the use of decorated paper for calligraphic and communication purposes declined. Fabric designers took up the craft. In prior centuries, with the primary use of decorative paper as a showcase for calligraphy, the interplay of positive (decorated) space and negative space (or ma in Japanese) was important for the overall balance of the work and the decoration was not meant to be so prominent that it interfered with the calligraphy. For kimono makers and fabric designers this was not the case – more uniform coverage of the silk was desirable, so the suminagashi patterns changed (see Gallery). I think this approach strongly influenced the approach to suminagashi papers in the 19th and 20th centuries, leading to the typical patterns seen and made today.

This stop-action video demonstrates the contemporary approach and pattern.

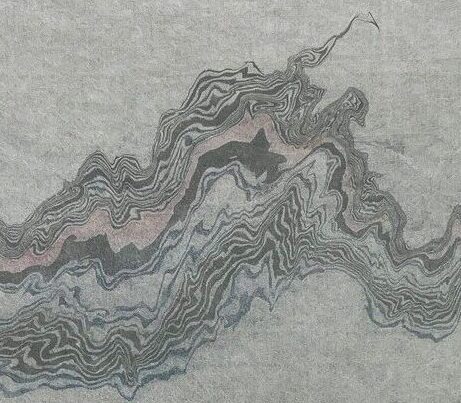

Below is the completed paper.

As discussed above, this type of pattern is relatively new when compared to the 900-year history of suminagashi. Here the decorated paper is the desired outcome rather than a more subtle form of decoration of a paper whose chief purpose is to support or enhance what is primarily a vehicle for poetry and calligraphy – but that is really what suminagashi was for over 600 years and is discussed in the next section.