The gallery includes both historical examples of suminagashi, and links to museum pieces. The gallery provides a visual view of the evolution of the art from the earliest known works to the present, arranged roughly by century/period. In many of the examples, suminagashi is only one of a number of other decorative elements (most commonly with the addition of gold or silver decoration) used as a background to the primary focus of the work – the poetry and calligraphy. From the 12th century through the 16th century the patterns were relatively straightforward although most examples show some evidence of use of the dispersant brush to compress the rings and alter the shape of the initial pattern. It is not until the Edo period (1603-1868) that, along with continued use of the dispersant brush to shift and compress the rings or expand the negative space, you see a wider variety of patterns, including a jagged appearance to the pattern made by fanning the ink rings, an appearance described as “slowly running streams coursing through fields” (Narita p. 72), and the use of color (indigo or dayflower for blue and, most likely, safflower for red) along with the sumi ink.

In the 19th century, the suminagashi technique was applied to silk for kimonos and there was a need for more uniformity in pattern over the long length of fabric – kimonos are made from one length of fabric. To achieve this uniformity, the patterns and the techniques changed significantly (see Suminagashi-zome). As can be seen in the examples shown below, they bear little resemblance to the classic suminagashi patterns. Nowadays, it seems that, in Japan, fabric artists have developed a hybrid system for what is still referred to as suminagashi. Instead of a pure water bath, water with a thickening agent is used, similar to western marbling, to better stabilize the pattern over the long length of fabric to be marbled, and the resulting patterns are closer to western marbling patterns than suminagashi (see the following: Suminagashi Kimono Marbling – Day One Continued – Ruth Bleakley’s Studio and Sonobe Dyeing).

The historical examples that follow are below their respective descriptions and commentary. I will be adding additional images or linking to them as I am able to locate them.

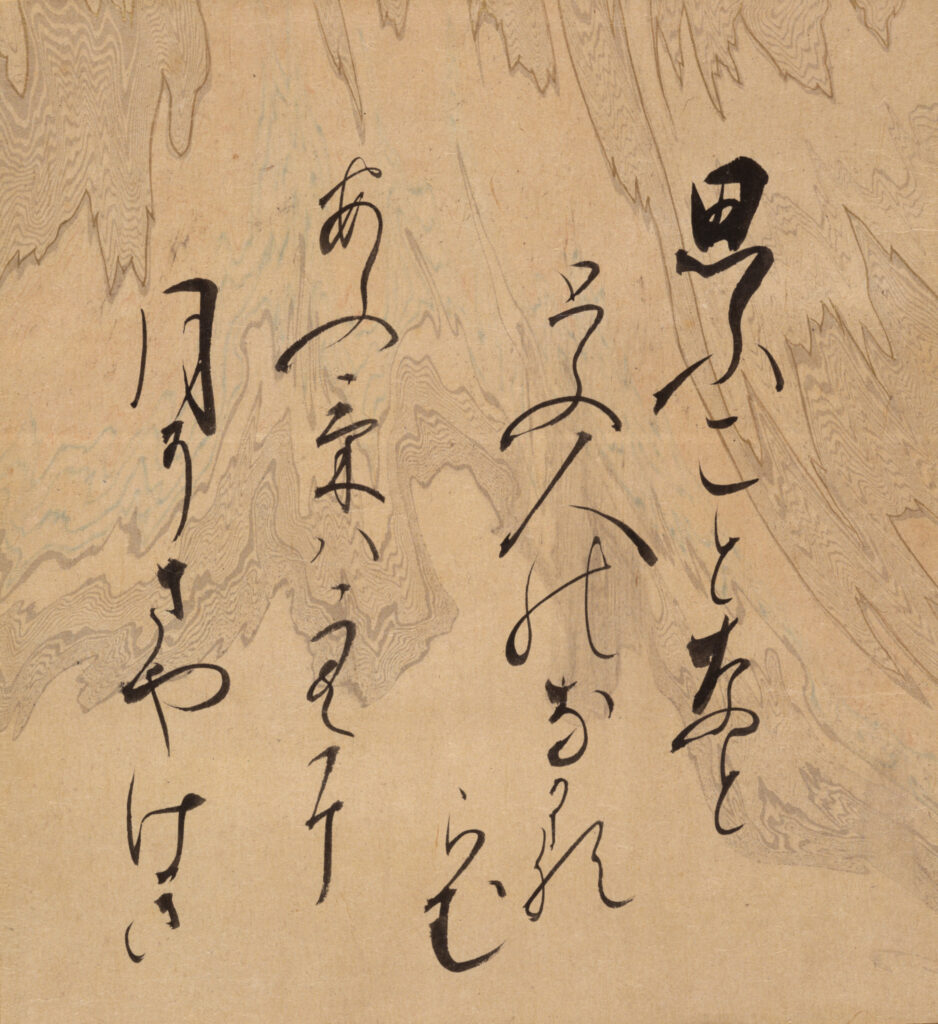

Sanjurokunin Kashu, early 12th century.

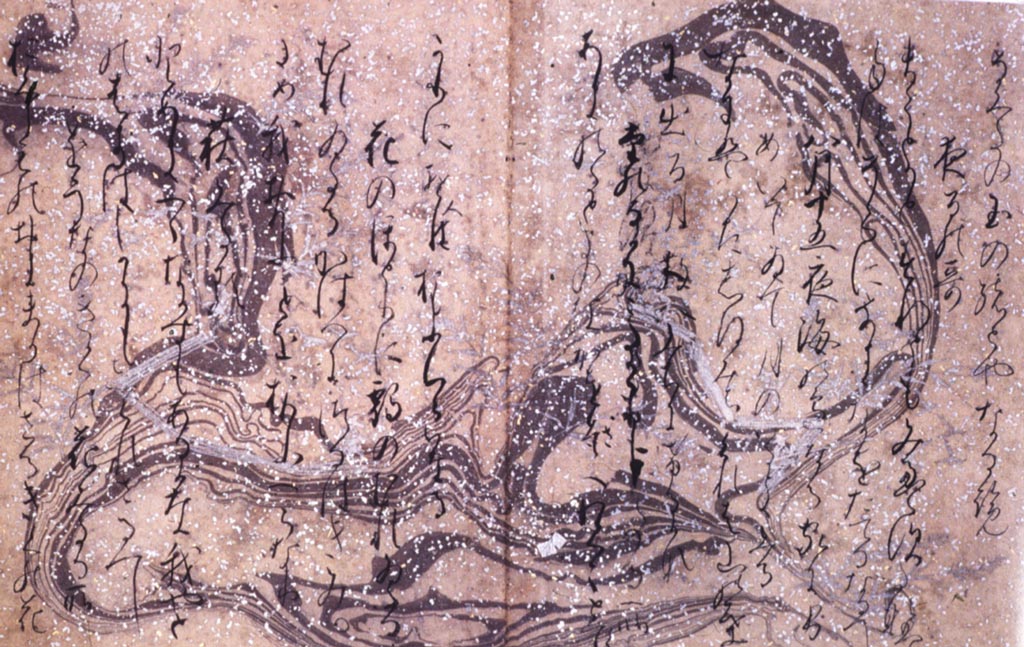

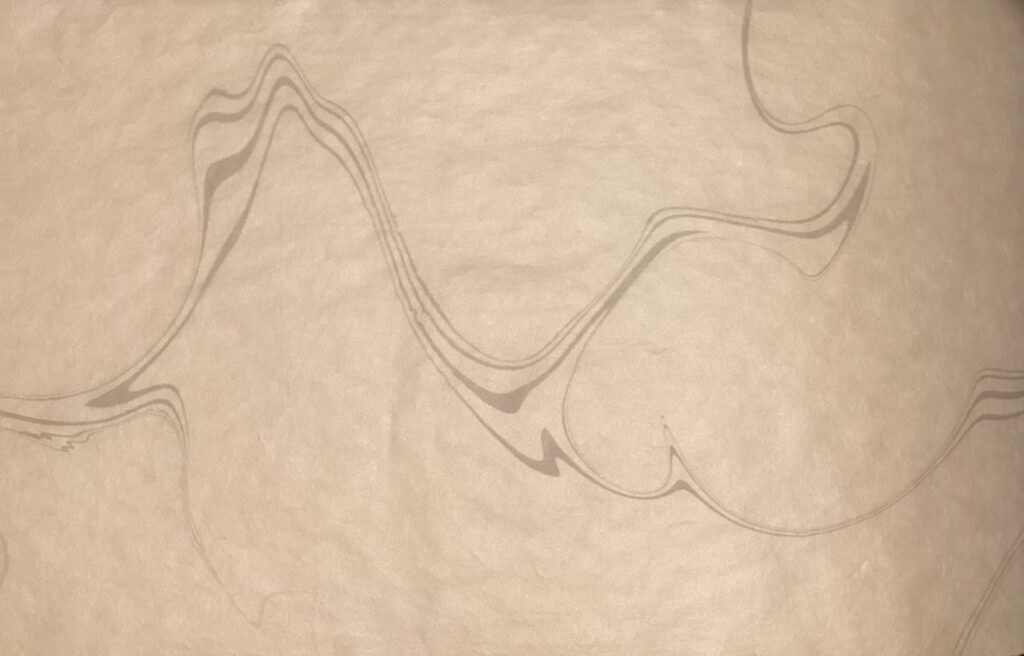

Below are two pages from a Fan Shaped Book of the Lotus Sutra, dating to the 12th century, in the Tokyo National Museum. Photo source:

Integrated Collections Database of the National Institutes for Cultural Heritage, Japan (ColBase). A variety of decorative techniques are used and four of the pages (#9, 15, 17, 19) include suminagashi, #9 and #15 are shown below. The suminagashi pattern was compressed and shifted in order to give it the wind-like sweep across the pages.

Here is a link to a poetry fragment in the Kyoto National Museum. The poetry/calligraphy with suminagashi background is found in a Tekagami (a personal/family album of exemplary calligraphy and poetry, the collected examples could span many centuries) – see, also, the example of additional Tekagami below. This specimen – taken from the Tada Edition of the Shinkokin Wakashu (New Collection of Poems Ancient and Modern) dates to the early 12th century.

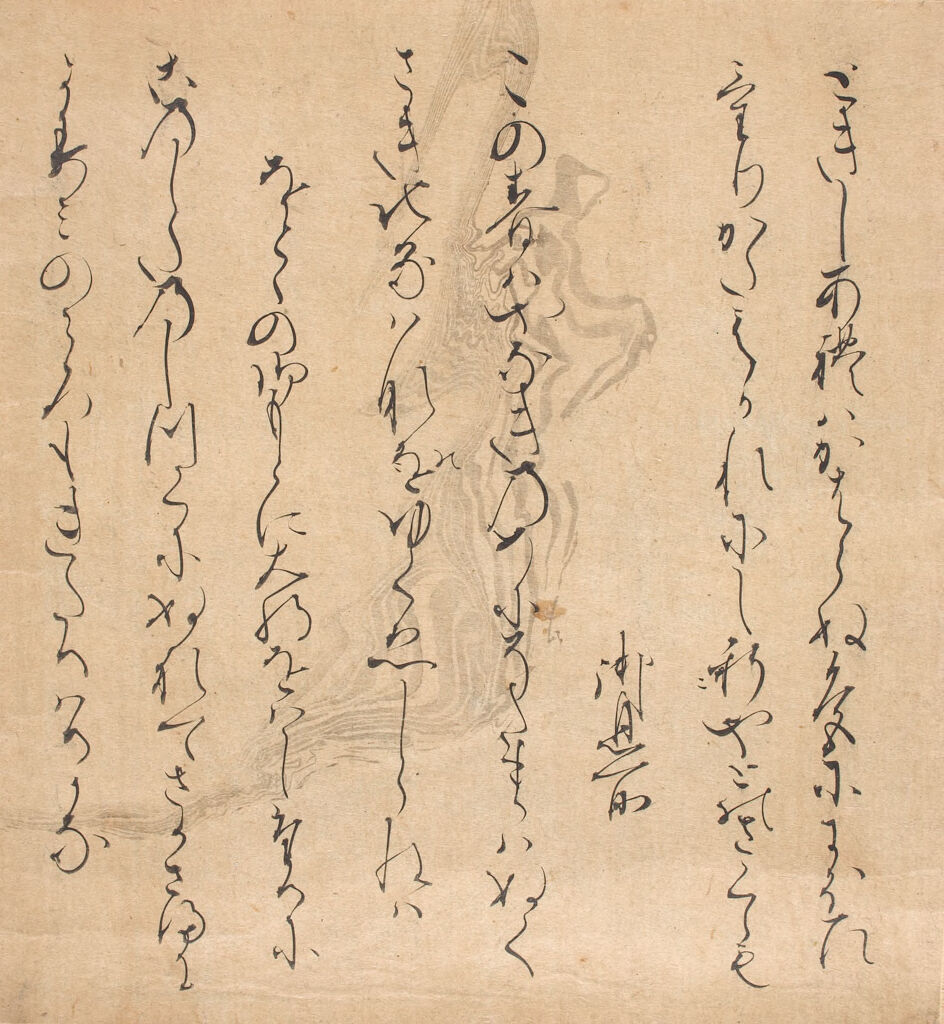

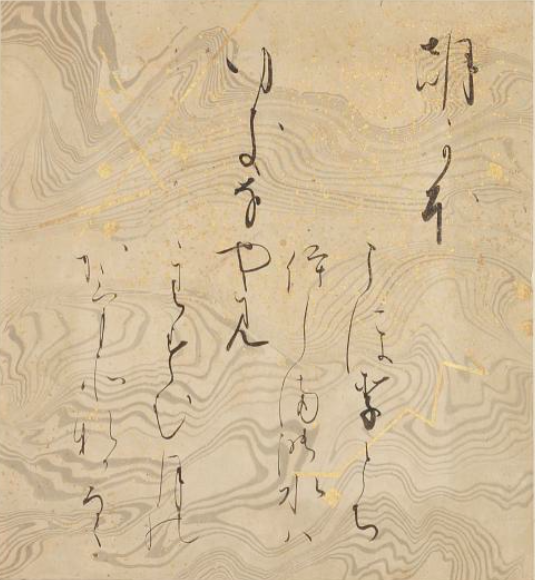

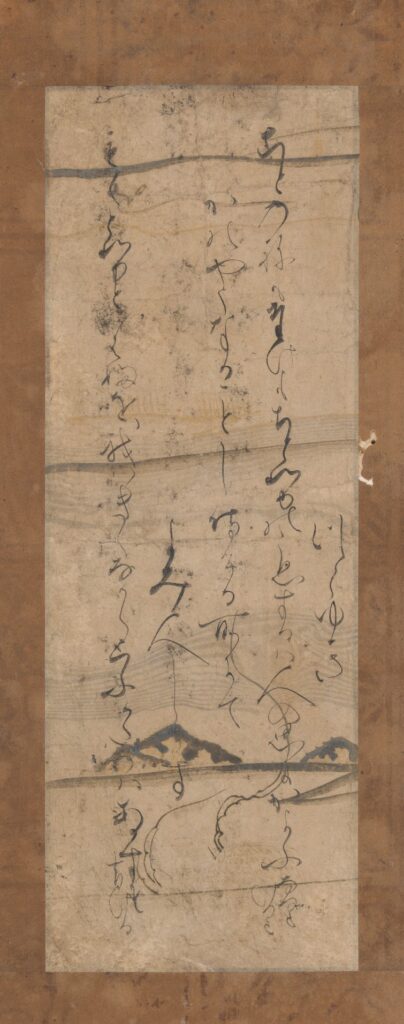

Three Waka Poems (Sanshu no waka) from the Tale of Genji (Genji monogatari). Attributed to Fujiwara Tameie, Japanese (1198 – 1275), Harvard/Sackler Museum 1985.397. 13th century.

Here is another example of suminagashi that was previously exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. It is found in the “Exile to Suma” chapter of The Tale of Genji, this volume, described as one of the earliest known copies of the novel, dating to the mid-13th century. The book has been returned to the lender so the image cannot be enlarged in order to see the pattern more clearly.

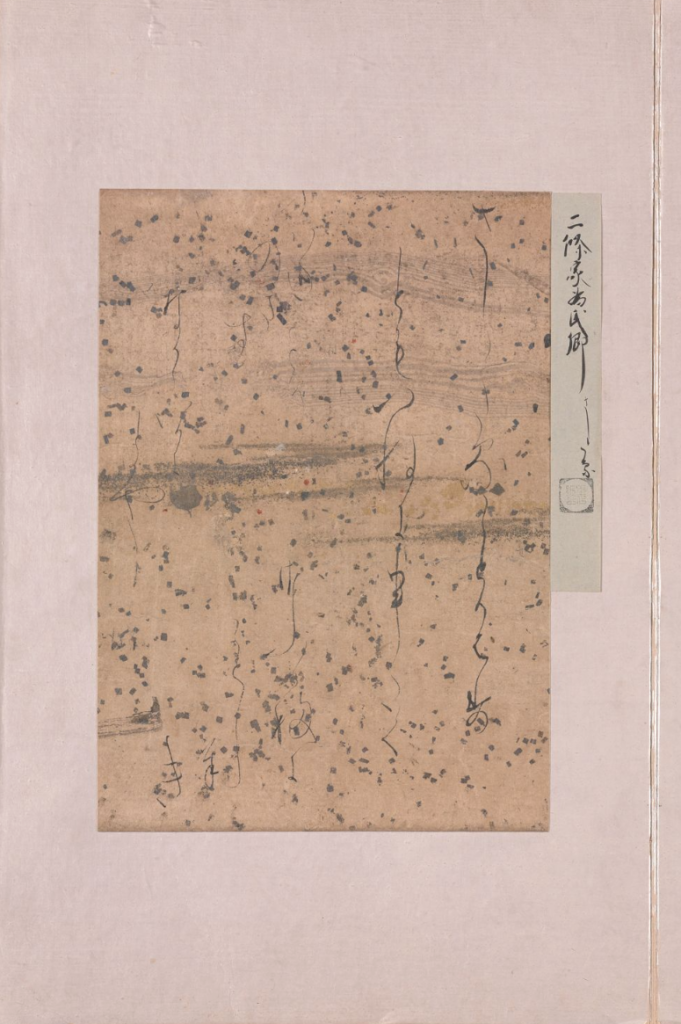

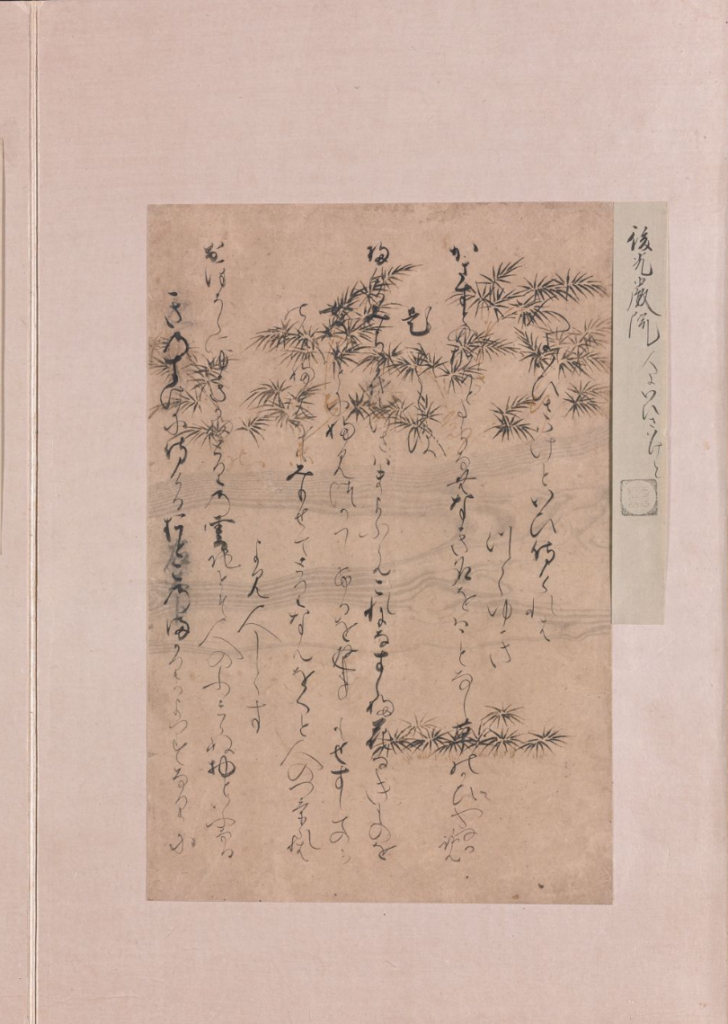

Another tekagami is in the possession of Yale University, The Tekagami-Jo album. It contains two specimens of calligraphy containing suminagashi decoration: #45 is attributed to (calligrapher) Nijō Tameuji (1222-1286), Kamakura period, 13th century. The second specimen, #10, is attributed to (calligrapher) Emperor Go-Kōgon (1338-1374), Nanboku-chō period, 14th century. For a view of the entire album, see The Tekagami-jō 手鑑帖 Project.

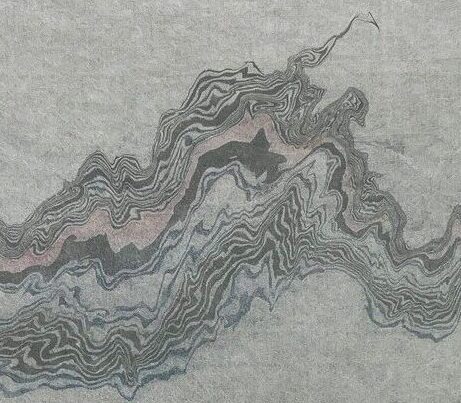

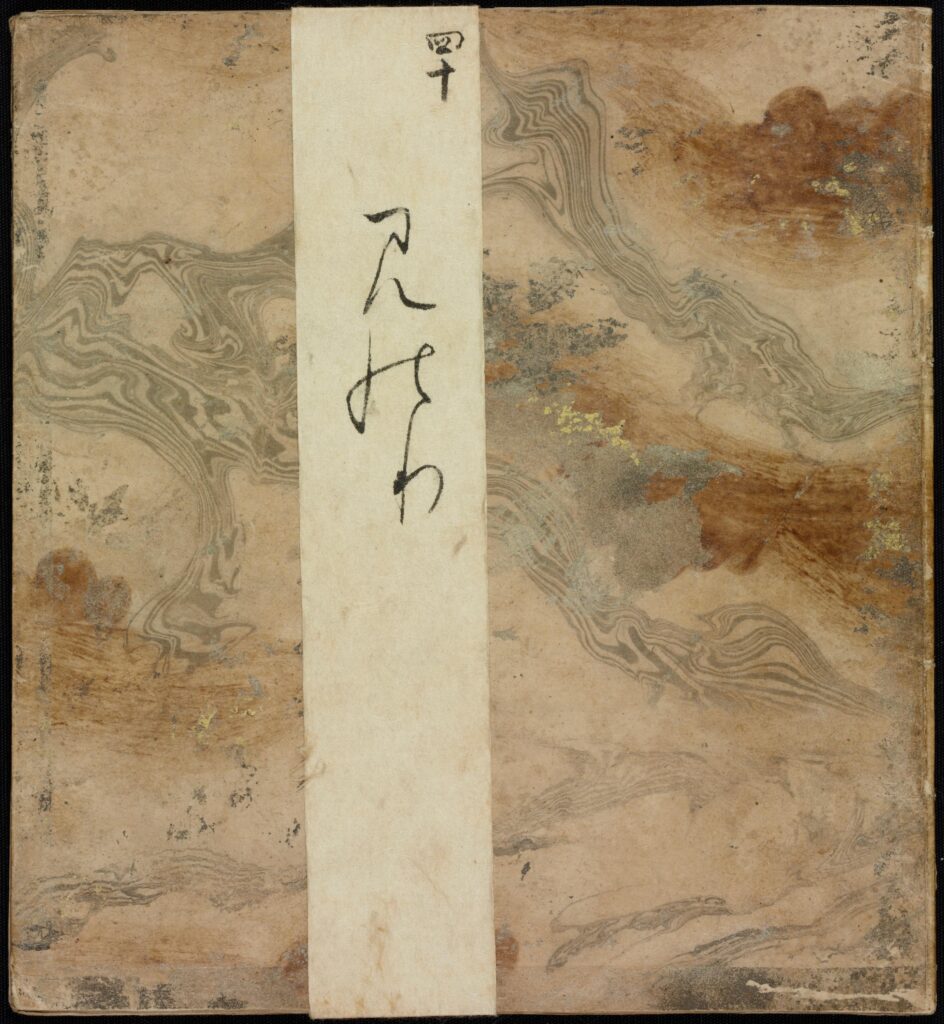

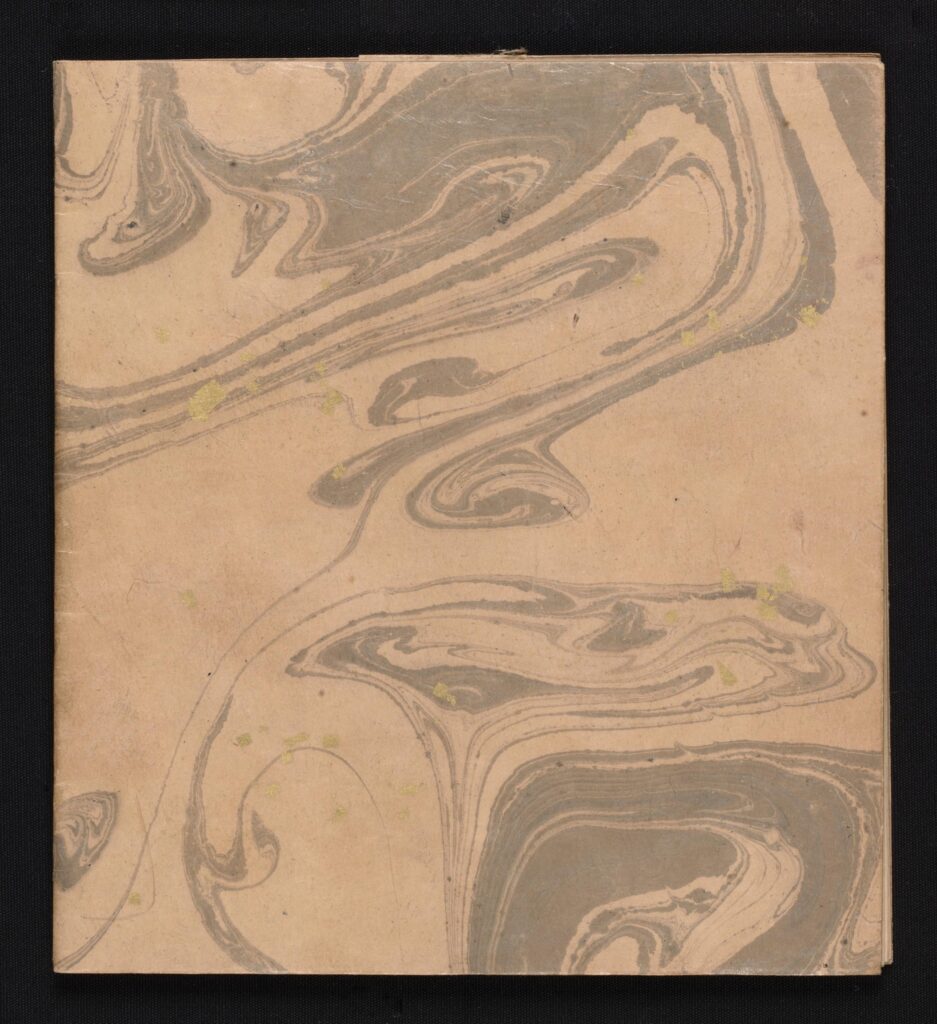

Below are the covers of two chapter books from The Tale of Genji – two of a number of chapters all arranged in separate book form – housed in the Tokyo National Museum. All the volumes have suminagashi on the front and back covers. These date to the Muromachi period, 15th to 16th century, some have gold flake (sunago) and small gold square decorations (kirihaku) in addition to the suminagashi. Photo source:

Integrated Collections Database of the National Institutes for Cultural Heritage, Japan (ColBase).

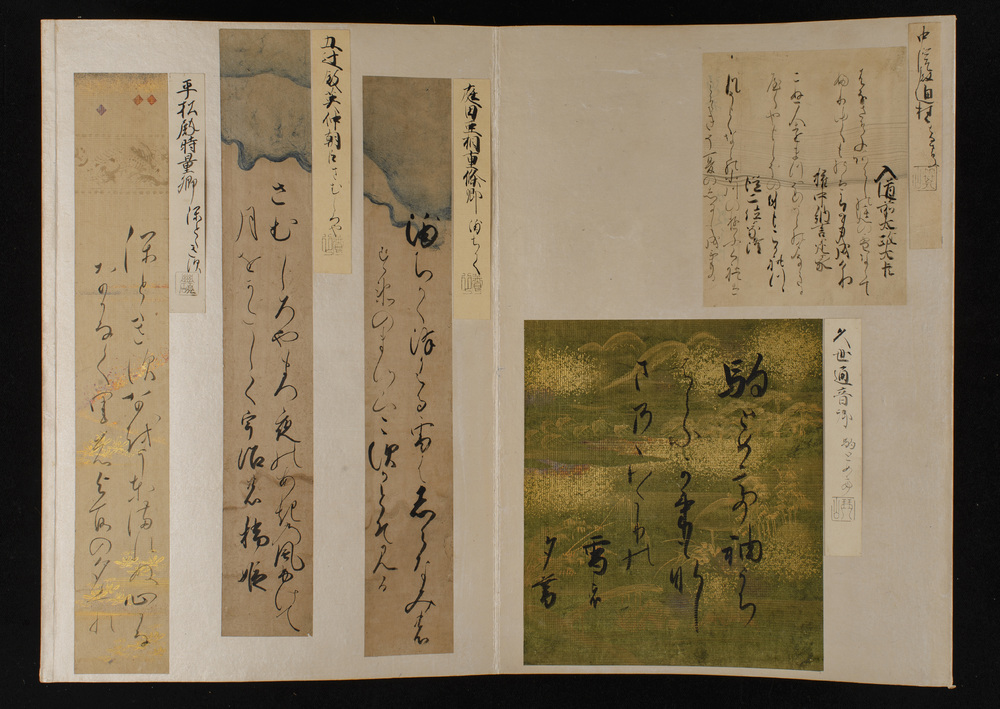

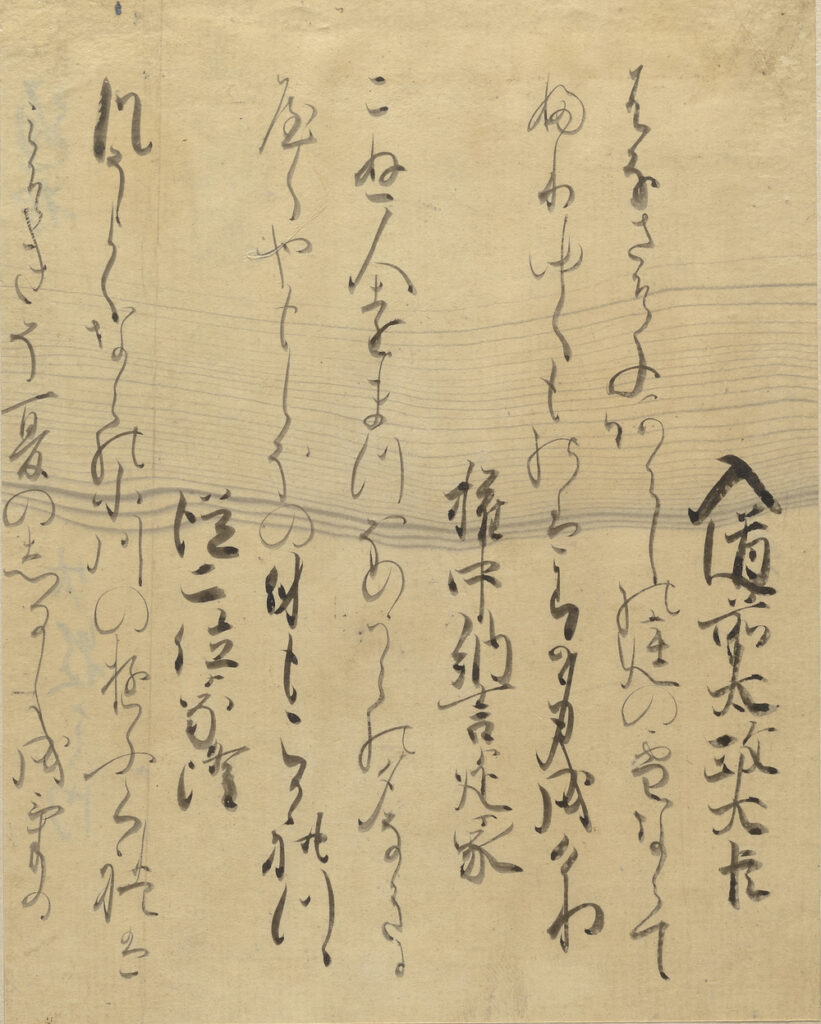

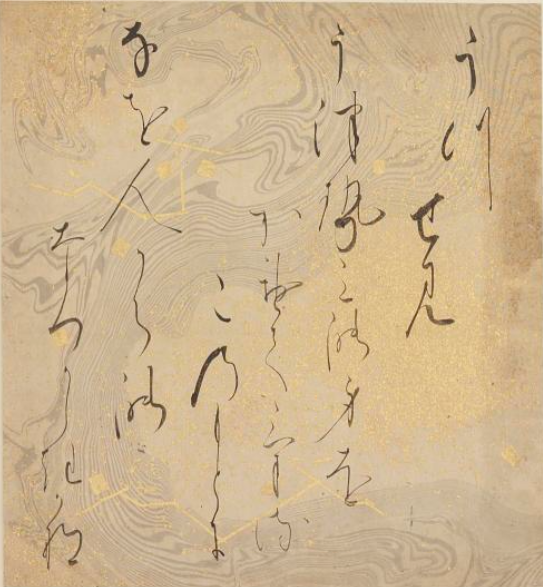

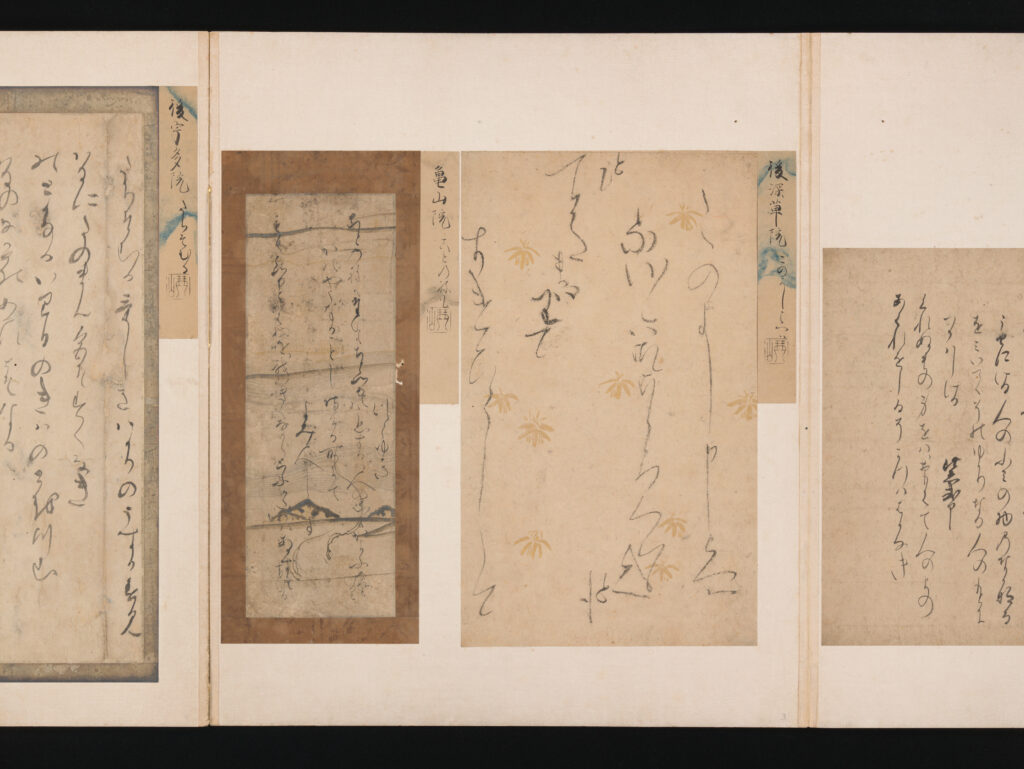

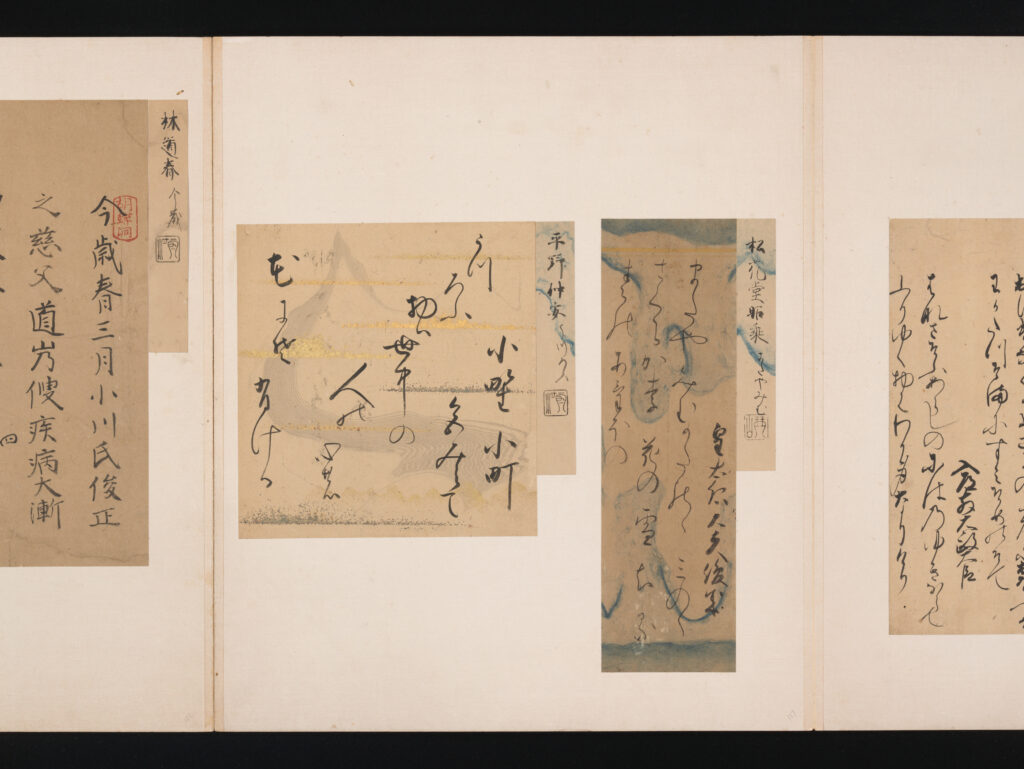

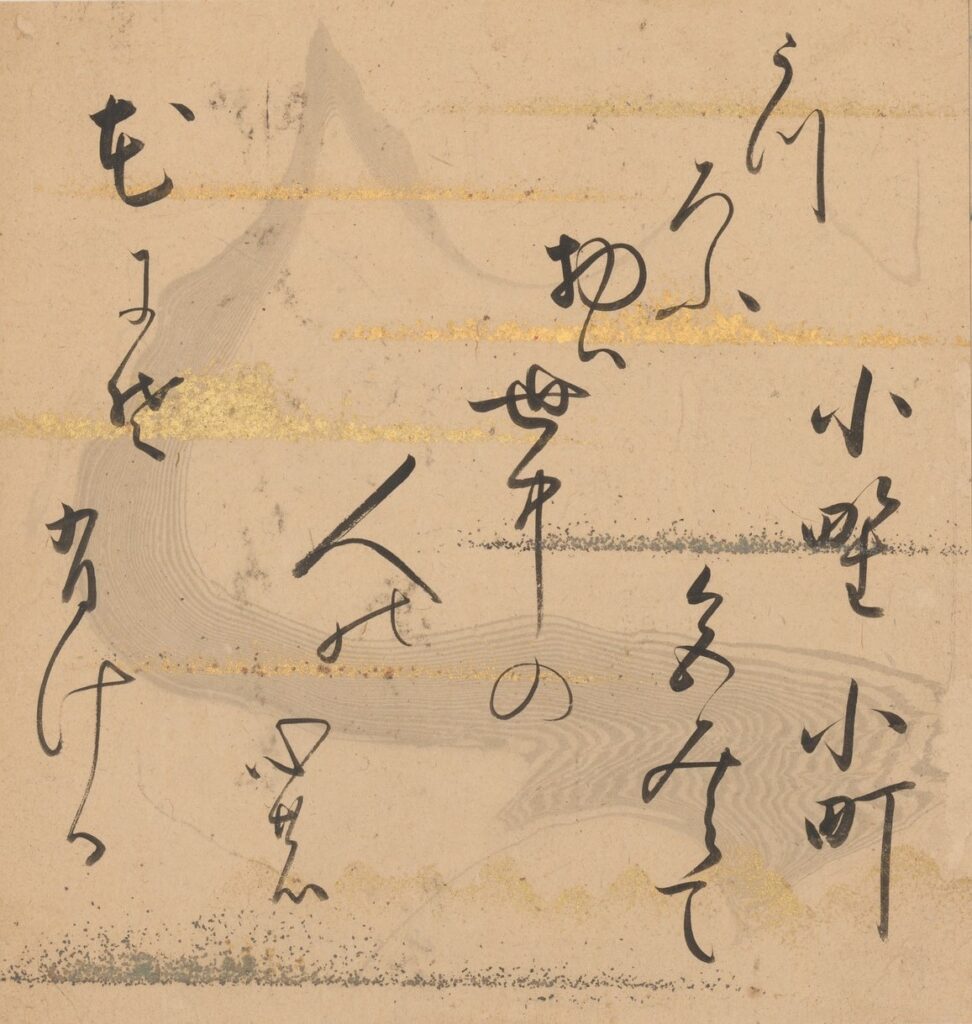

A Mirror of Hands Album (tekagami 手鑑), back side, pages 095-096, assembled early 19th century. A piece with background suminagashi is located in right upper corner and is also shown below. University of Oregon. Attributed to Naka-no-in Michimura (1588-1653), 17th century.

Below are two pages of suminagashi with gold squares (kirihaku), gold flake (sunago) decoration from Album of paintings and calligraphy depicting scenes from The Tale of Genji. Early 17th century. Smithsonian National Gallery of Asian Art.

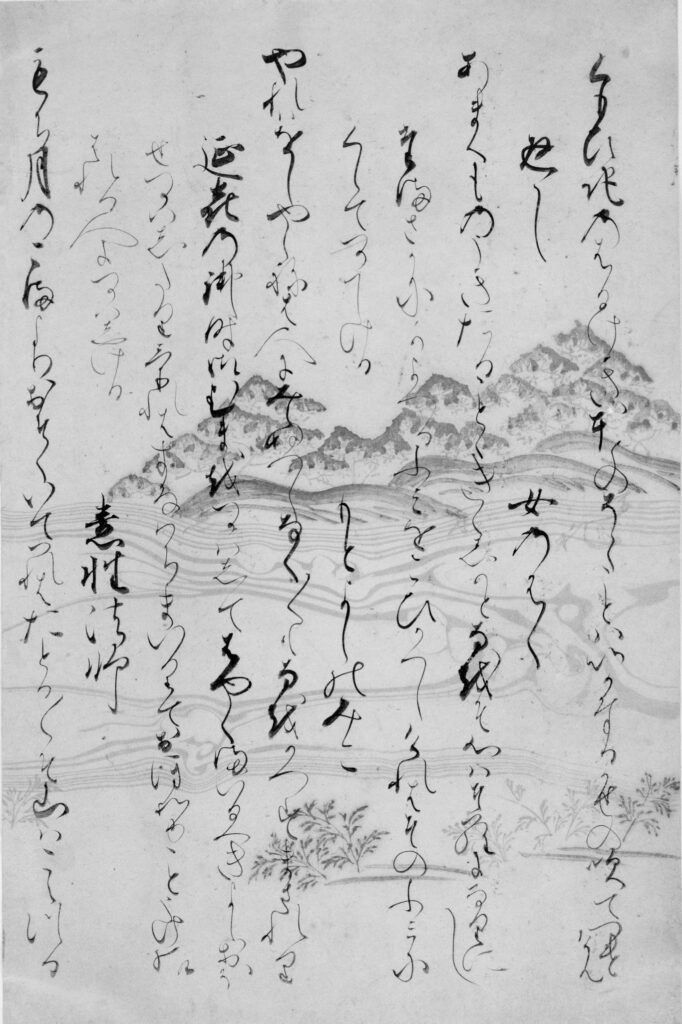

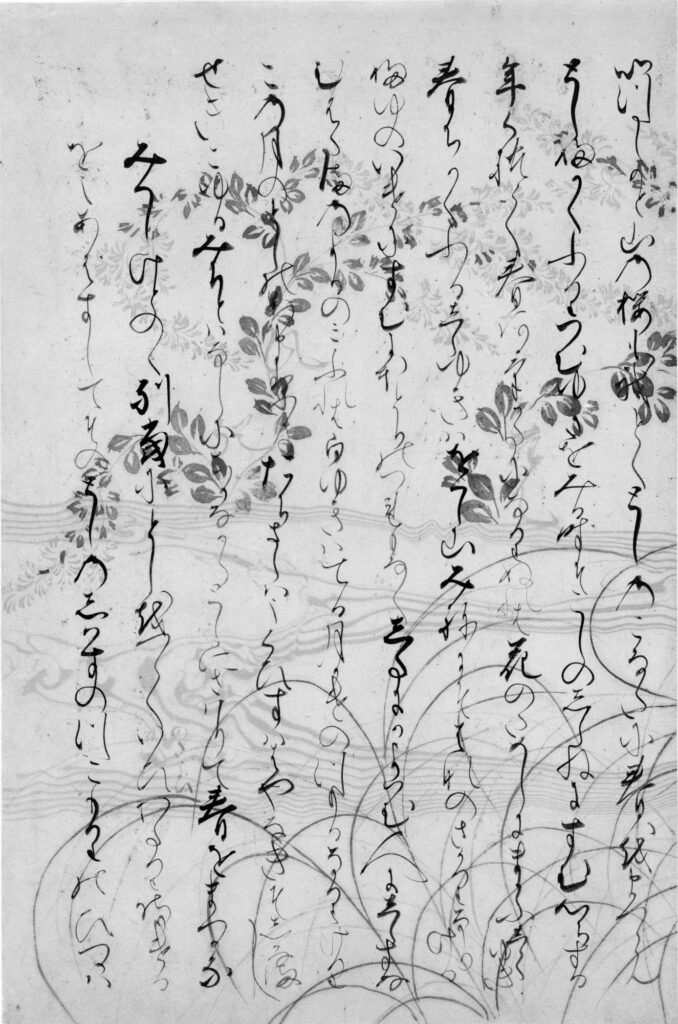

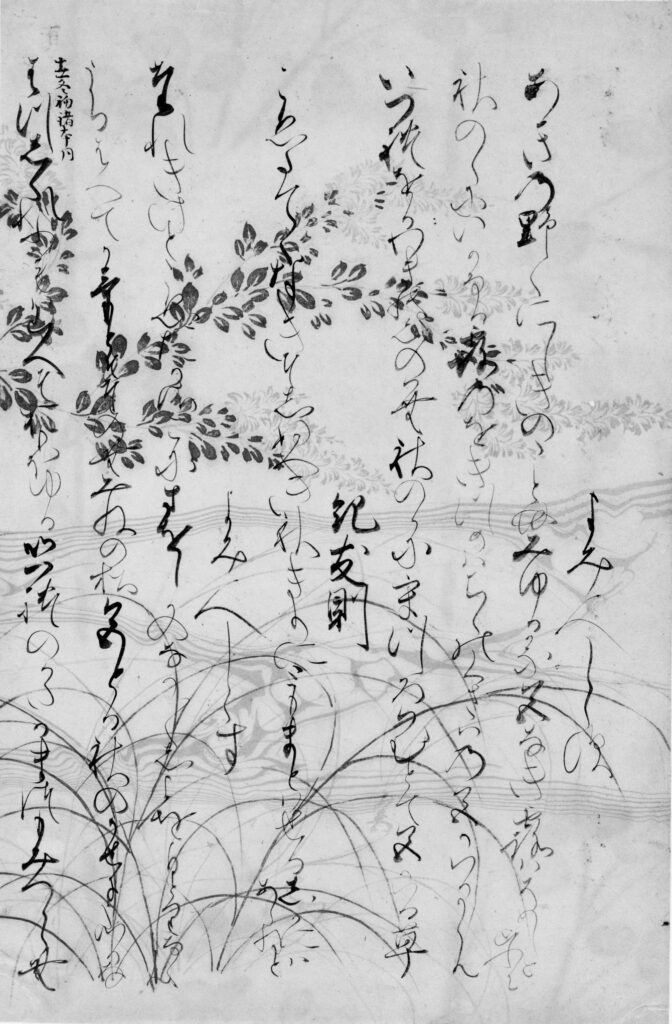

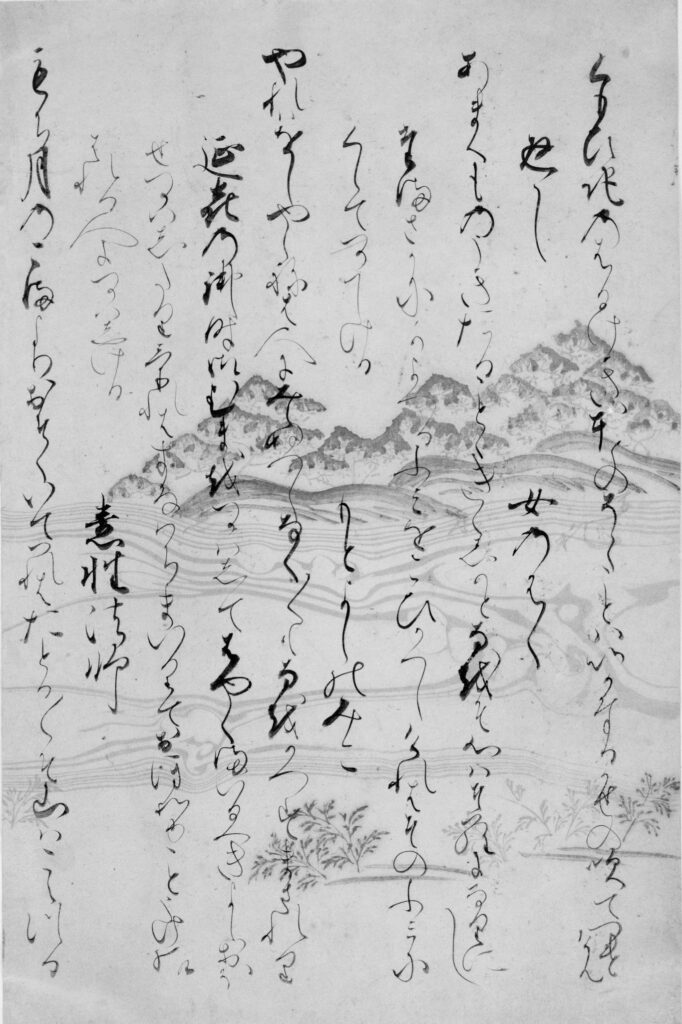

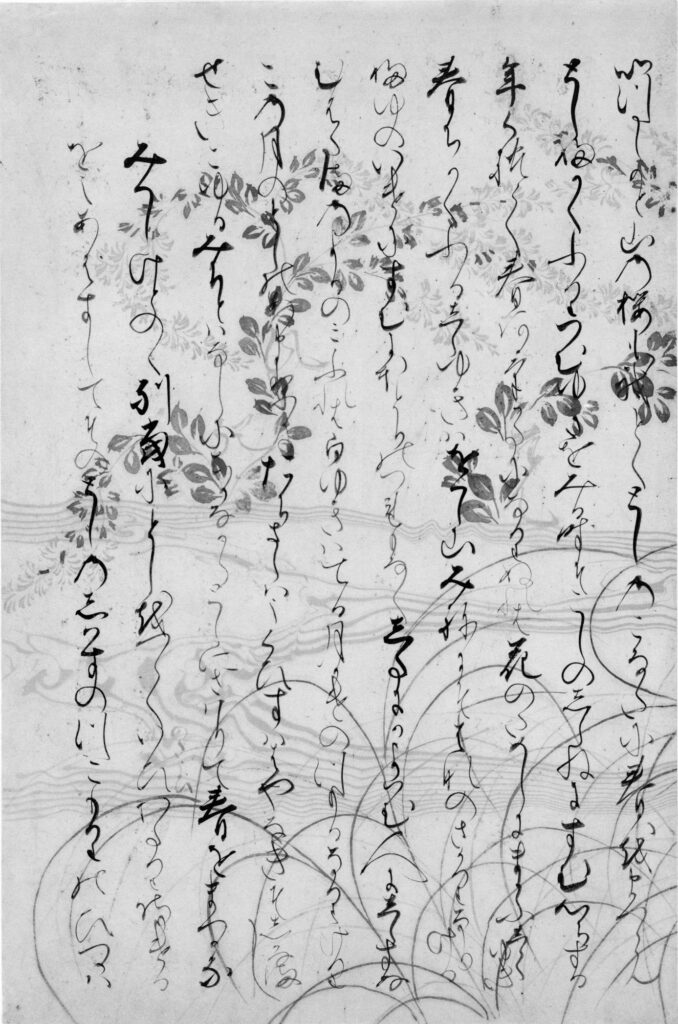

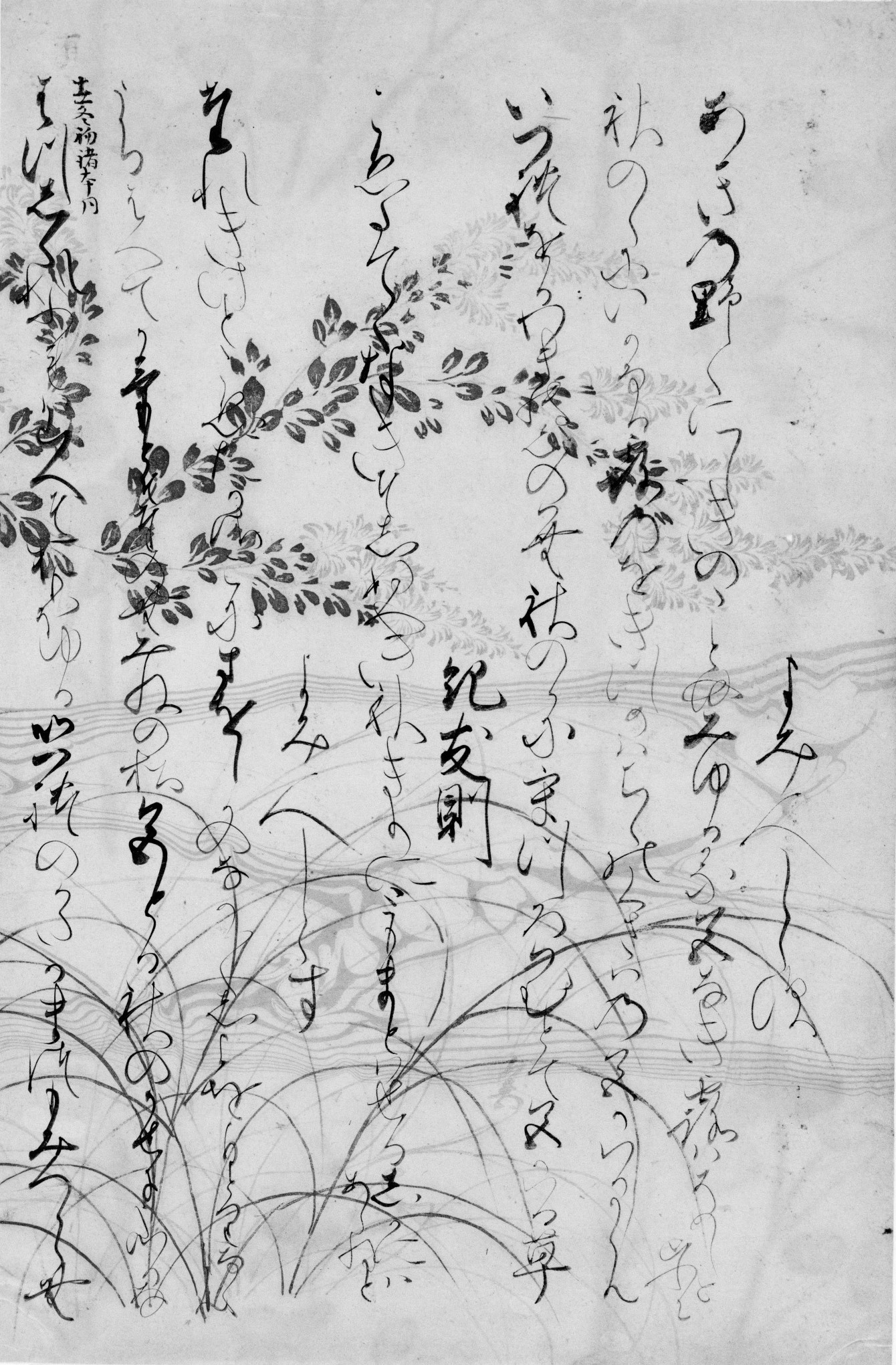

The following three examples, dating to the early 17th century, in the Virginia Museum of Fine Art are leaves from an album of ten leaves featuring calligraphy of poems from the Collection of Ancient and Modern Poems (Kokin Wakashu); ink, gold, and silver with suminagashi – unfortunately the images are only black and white. The dimensions of most of the pieces are approximately 9 5/8 × 6 5/8 in. (24.45 × 16.83 cm) as is the case for the sheet immediately below. Most likely these were cut from a scroll, with some sections missing. When leaves 68.52.2, 68.52.7 and 68.52.3 are placed next to each other the continuity of the suminagashi pattern and the superimposed decorative elements is evident. Other leaves do not match up as well and likely sections of the scroll are missing. While most suminagashi was done on a small scale, this piece, and the scroll in the Harvard Sackler Museum shown below (and discussed in Advanced Techniques) show that some large scale suminagashi work was also done, particularly in the 17th century.

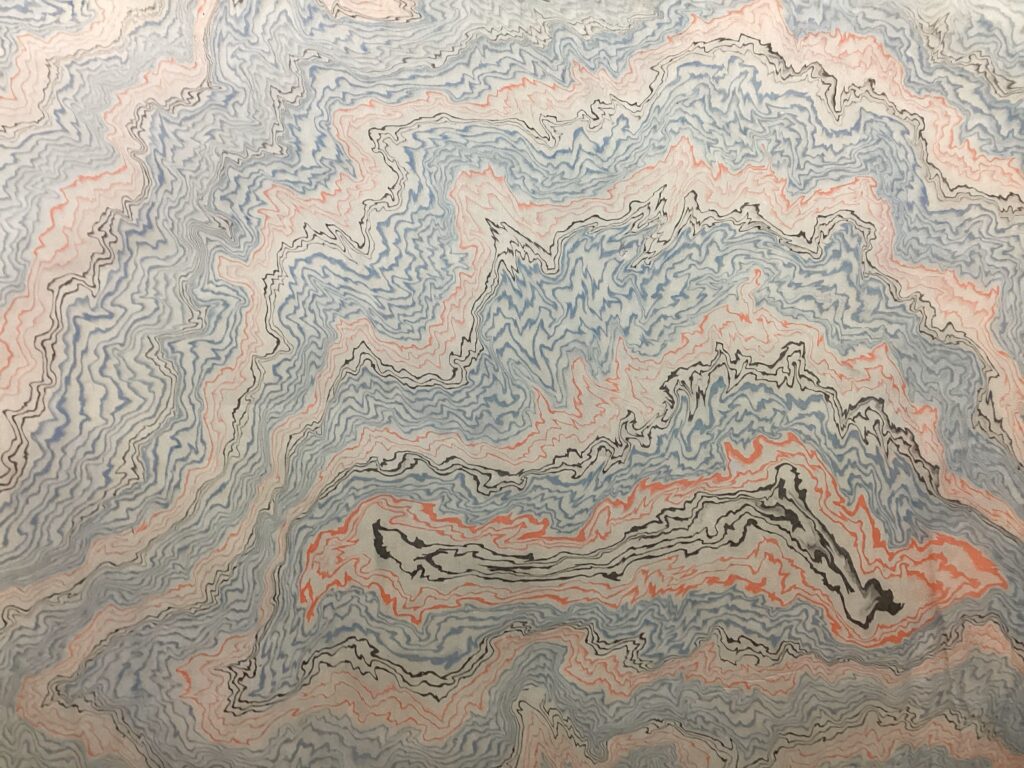

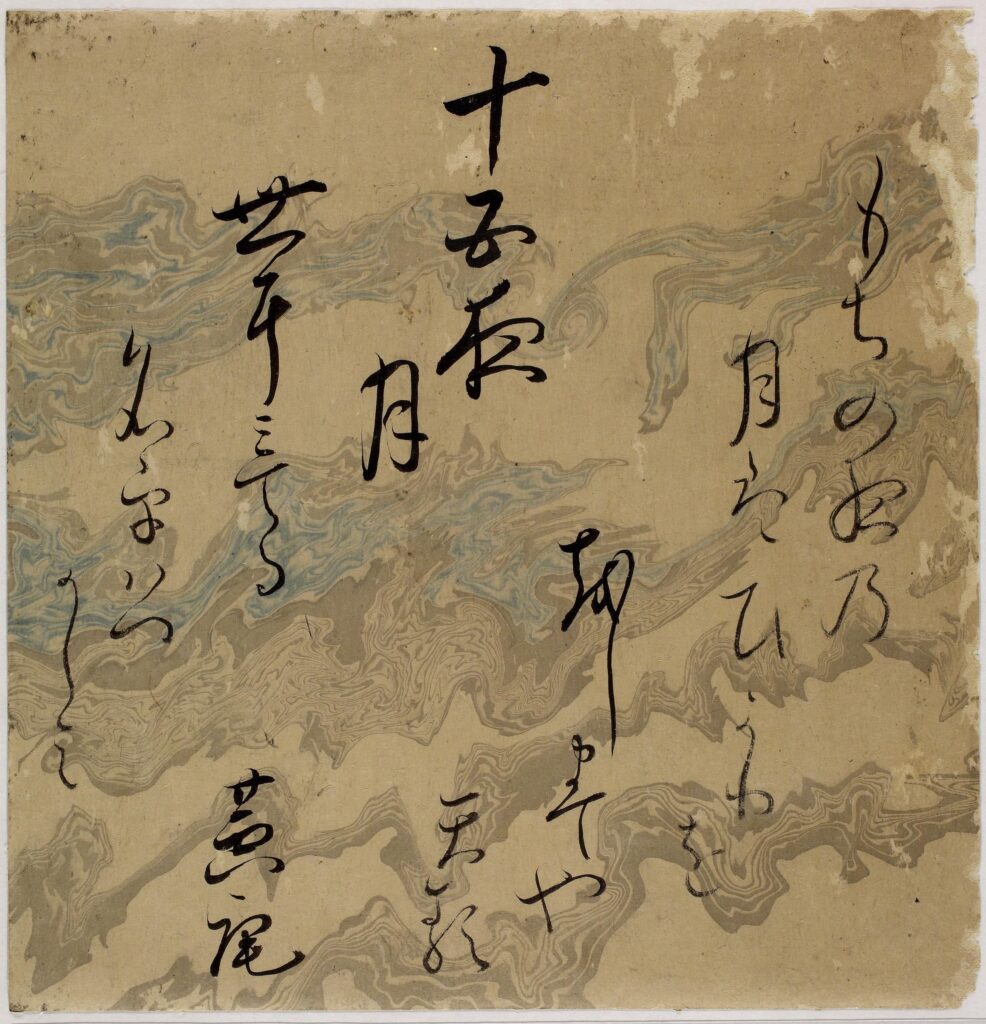

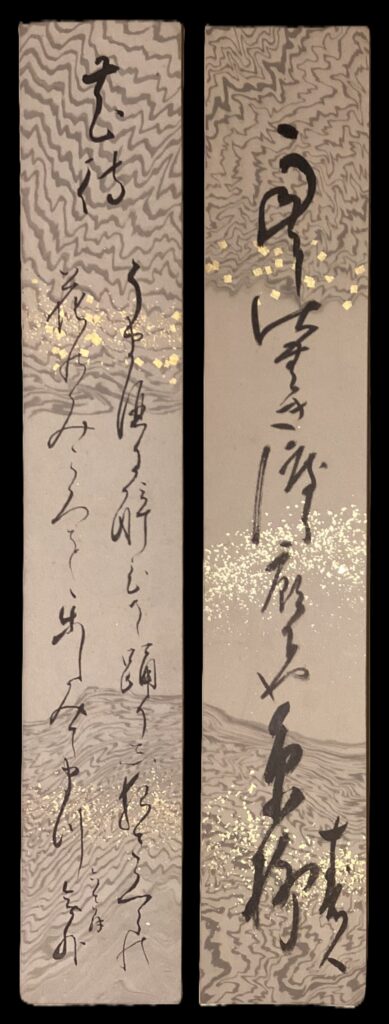

Next are two Waka Poems on suminagashi by Tokugawa Iemitsu (1604-51), Edo period, 17th century. Tokyo National Museum. The upper work includes the use of blue and red (very faded), the lower also has some very faded red – about the earliest inclusion of those colors that I have seen, also the earliest example of the use of the fan to give a jagged appearance to the pattern. Photo source:

Integrated Collections Database of the National Institutes for Cultural Heritage, Japan (ColBase).

Here are two books from the 17th century. The first (https://www.fl-keio.info/fl_img/course05/detail/091_To298_1_001.html ) is a book of poems from a poetry contest (uta-awase), date not specified other than early Edo period. Suminagashi is present on multiple pages of the book, patterns similar, although simpler, to the Genji volume above.

The second (https://www.fl-keio.info/fl_img/course05/detail/Private_Kokinwakashū_001.html) is one of 20 volumes of the Kokin Wakashū (古今和歌集, “Collection of Japanese Poems of Ancient and Modern Times”), this version of the famous poetry collection published in 1678. Here the suminagashi is on the book covers – most interestingly using both sumi ink and indigo – another early example of the use of colored ink that became more common later in the Edo period.

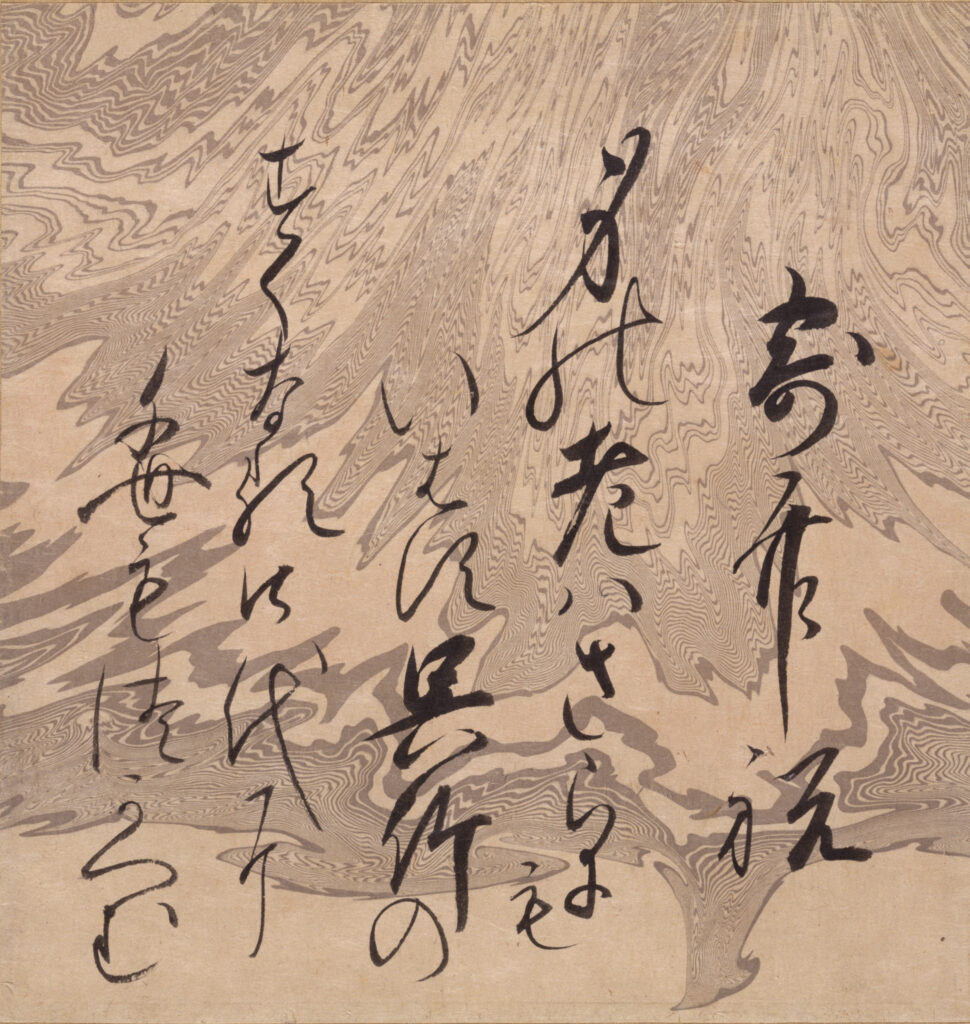

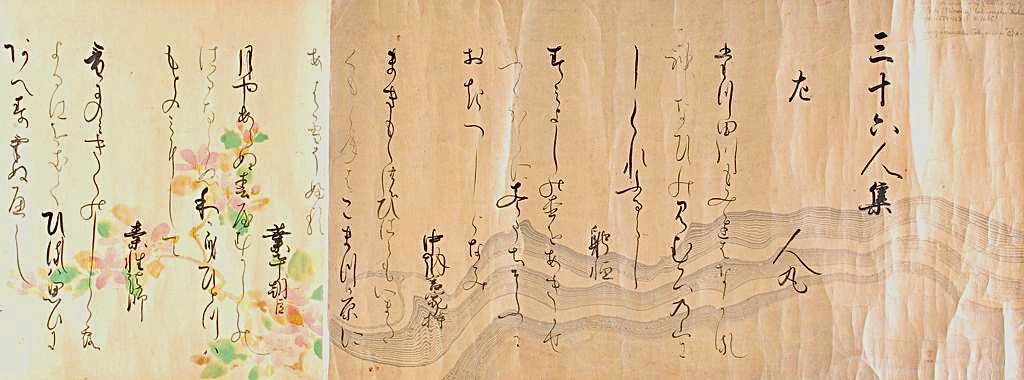

Poems of Thirty-six Poets (Sanjūrokunin-shū). Attributed to Shōkadō Shōjō, Japanese (Sakai 1584 – 1639). 17th century. Harvard/Sackler Museum 1985.545. I discuss this pattern further in the Advanced Technique page.

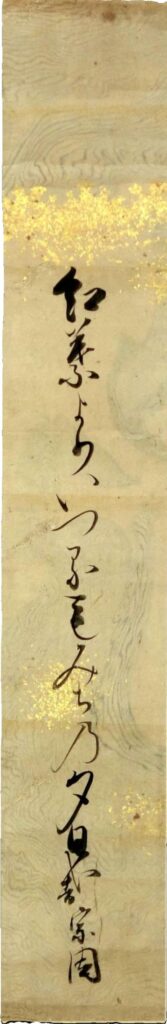

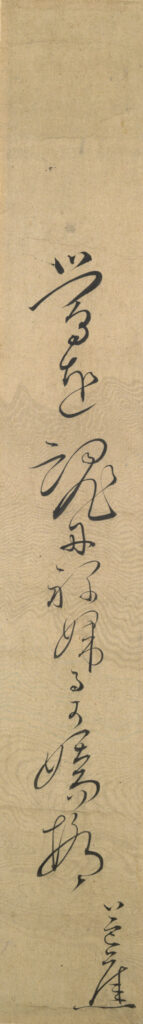

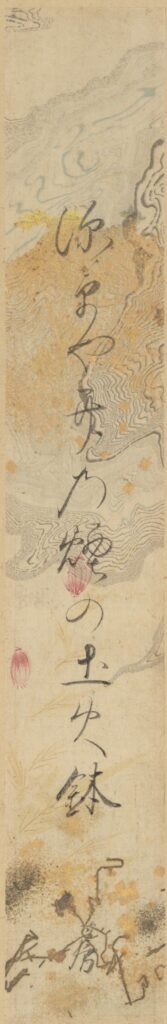

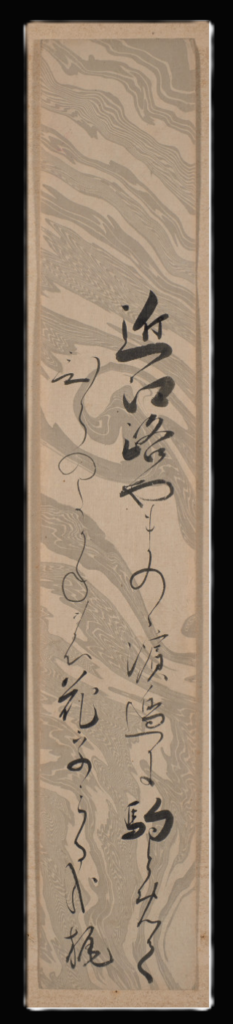

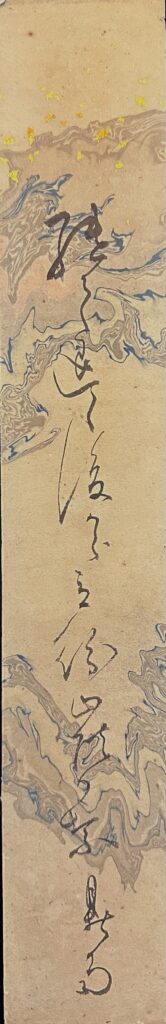

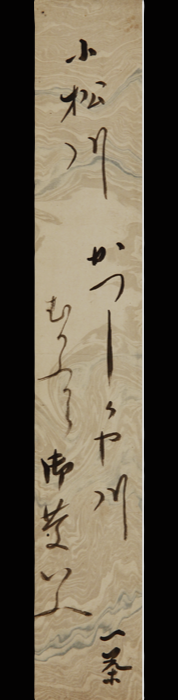

Below are three 17th century tanzaku with haiku poems by Soin on the left, Basho in center and Tomonori on the right. It is remarkable how similar the suminagashi patterns are on all three tanzaku. The suminagashi lines are very fine, the patterns are subtle, Basho’s most of all. This seems to have been the aesthetic for suminagashi in the 17th century as can be seen in the other papers above and below. The Basho tanzaku is in the Tokyo National Museum, Photo source: Integrated Collections Database of the National Institutes for Cultural Heritage, Japan (ColBase). The Tomonori tanzaku is in the Metropolitan Museum in New York.

Below are two pages from a tekagami, A Mirror of Gathered Seaweed (Mokagami), in the Metropolican Museum of Art, New York. A cropped image of the piece with suminagashi is below the respective pages. These are undated but based on the style of suminagashi I would suspect they are no later than the 17th century. The paper and style of the first one is very similar to those above in the Tekagami-Jo album at Yale so this one could be as early as 14th century.

Tanzaku late 17th early 18th century. Calligraphy/poetry by Kaji of Gion. Denver Art Museum.

Tanzaku, probably 18th century, showing the use of blue (probably indigo since it is still strongly colored) and red/pink, although that color has faded, is almost completely gone from the bottom lines of suminagashi. Personal collection.

Below is a piece measuring approximately 7X7 inches in the British Museum online collection. Probably 18th century based on the pattern. “From a folding album purchased from Messrs A A Godwin on 9 Nov 1880 and registered in the Sub-Department of Oriental Manuscripts as Or.2280.” This was likely a piece removed from a tekagami, i.e. “folding album”.

Tanzaku with haiku by Kobayashi Issa (1763-1828), late 18th, early 19th century.

Additional examples of early nineteenth century Tanzaku can be found on the Tanzaku page.

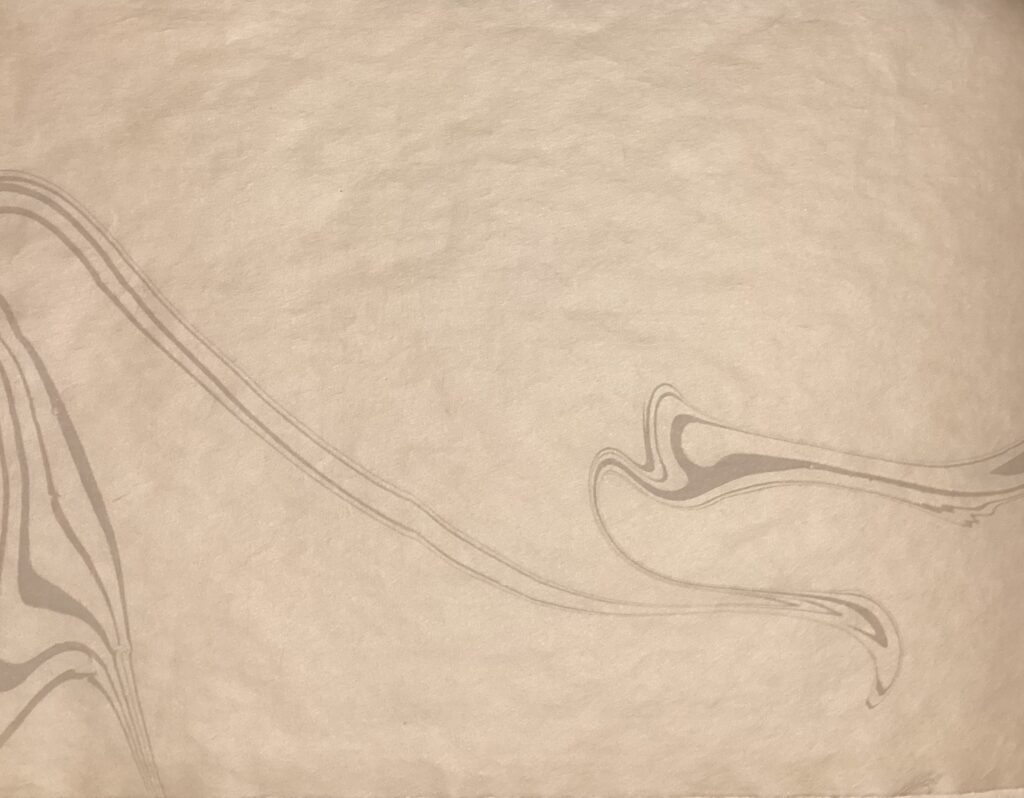

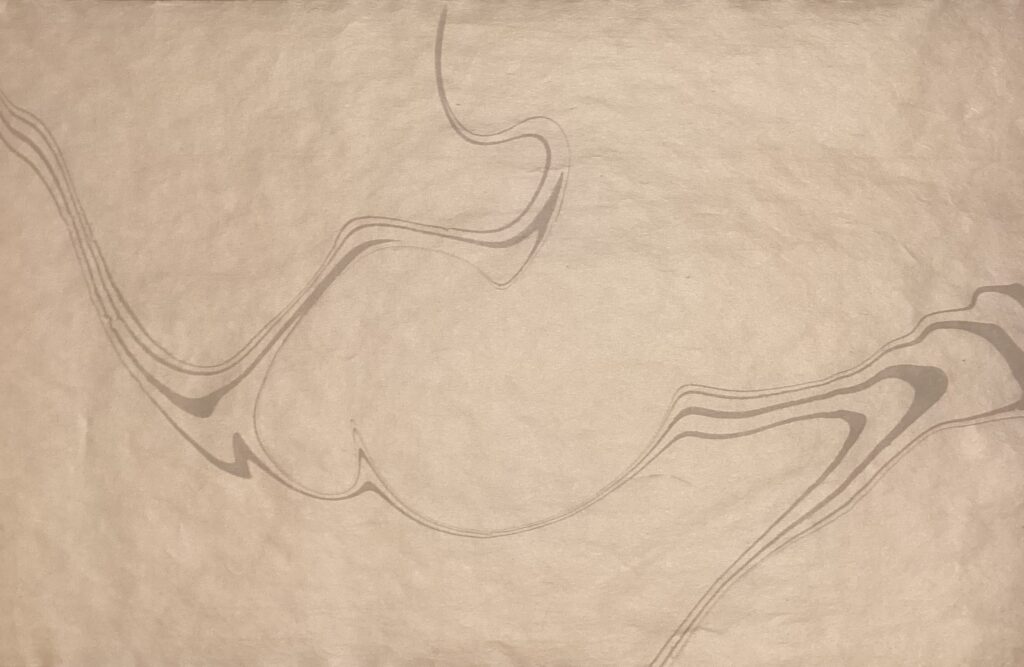

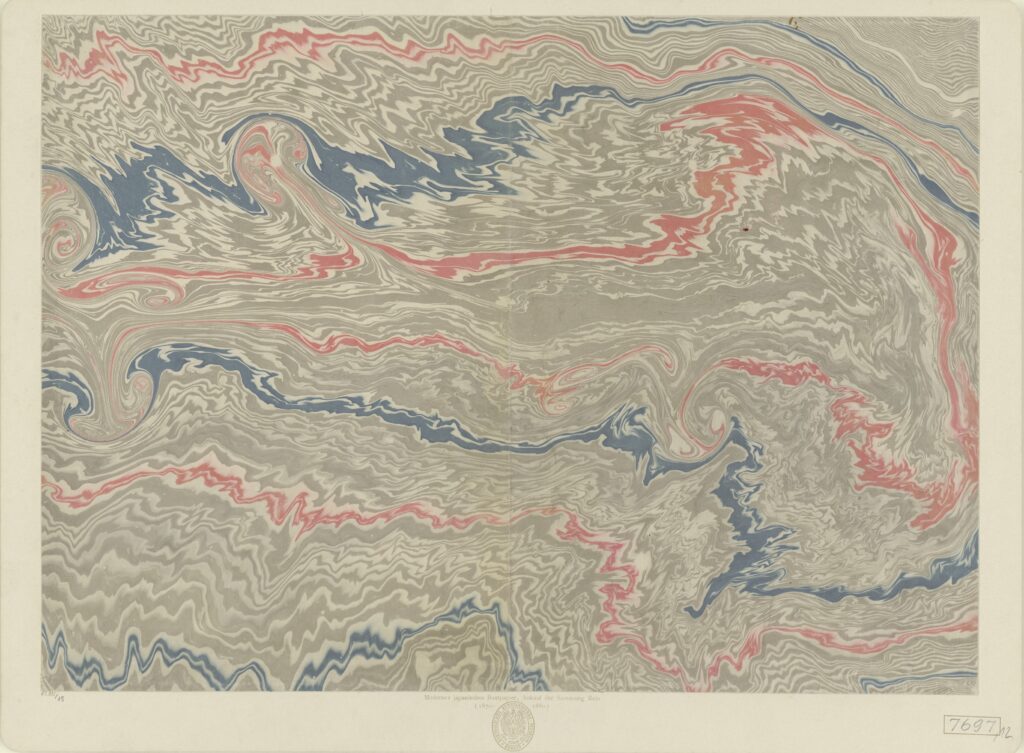

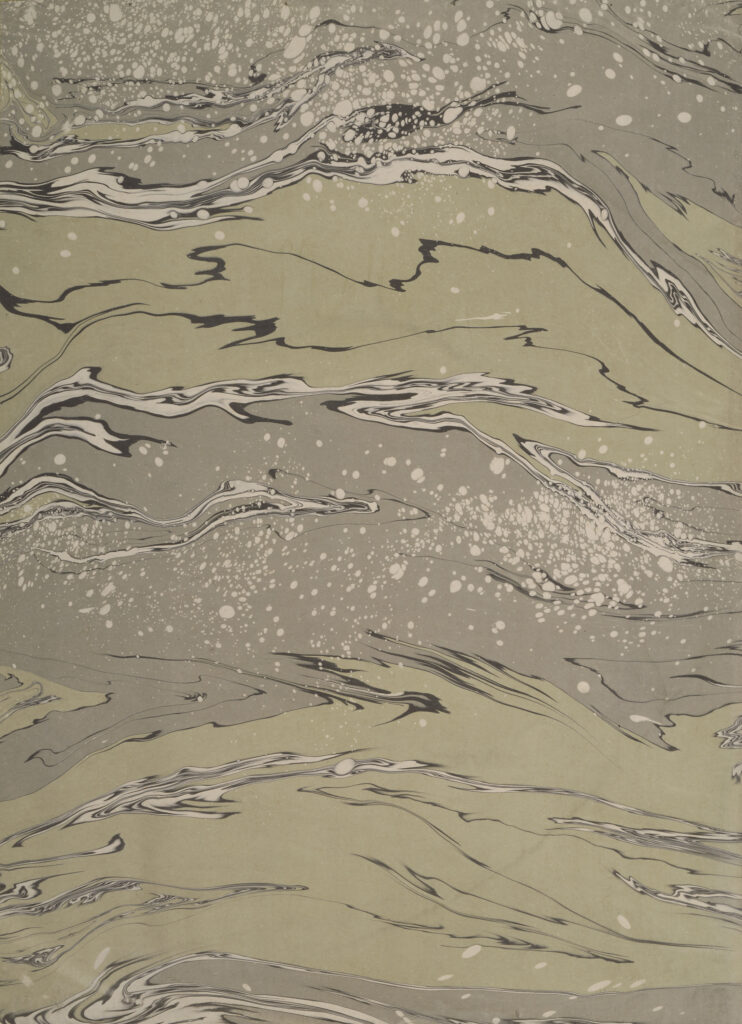

The following is a sheet of suminagashi dating to 1870-1880, unknown artist. This illustrates the evolution of suminagashi patterning in the late 19th century from paler patterns with more open or negative space to what I consider the “modern” style of suminagashi where the pattern and darker ink cover the entire sheet of paper. The paper is held in the paper collection of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kunstbibliothek, 35 X 48.7 cm.

Two Tanzaku, probably 19th-early 20th century, personal collection.

Below is a page from a Sample Book of Suminagashi Patterns. These are textile patterns, Meiji Period, 19th century. Kyoto National Museum No. IK105. You can see, again, how suminagashi has changed, reflecting evolution in the use of suminagashi, now for fabric, with the page filled with ink and minimal negative space. Photo source:

Integrated Collections Database of the National Institutes for Cultural Heritage, Japan (ColBase).

Suminagashi on silk haori jacket, overdyed, 20th century, personal collection.

Suminagashi on silk – the pattern is more prominent on the darker leaves but is present throughout the fabric – probably early 20th century.

Sheet of suminagashi by Tadao Fukuda, 21st Century. Until the time of his death, in 2021 at the age of 95, Mr. Fukuda was, to the best of my knowledge, the only professional suminagashi artist in Japan. He had no apprentices, and he kept his paint recipes secret, so there was no one to carry on the tradition and the studio has closed. Here is a YouTube link showing a nice video of his technique.