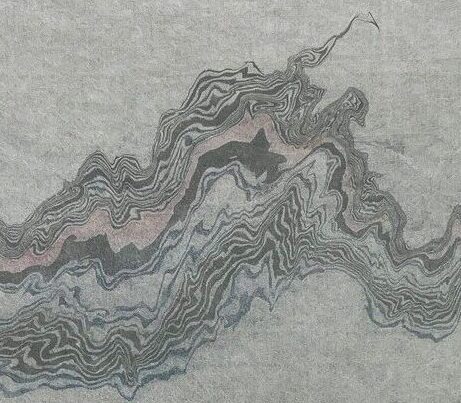

Suminagashi, 墨流し, translated as black ink flow, black ink floating, is a Japanese decorative paper technique that, at its most basic level, involves touching the surface of water with an ink-loaded brush (or brushes), allowing the ink to flow onto the surface of the water. The resulting pattern can then be gently transferred to paper by laying a piece of absorbent paper down on the surface of the water.

The development of the process is obscure since there are no written records addressing the fabrication of suminagashi patterns until the 19th century. Jake Benson published an excellent overview of what is known or speculated about the development of suminagashi, “Historical References to Marbling in East Asia.” in the 2005 Society of Marbling Annual Journal.

The most detailed information concerning the process deals primarily with suminagashi on silk. In the early 20th century, Tokutaro Yagi, the last practitioner of suminagashi-dyeing (suminagashi-zome), dictated a description of the tools, materials and procedures to a teacher at the Kyoto Technical Dyeing College. By the 19th century, with the shift to the use of suminagashi for silk decoration, the patterns, the process, tools and materials had become quite complex, utilizing materials and pigments/colors that had not been available previously. However, the patterns described are very different when compared to the classic ones of earlier centuries (see Historical Gallery). Robin Heyeck published the English translation of Suminagashi-zome in 1991.

Suminagashi was introduced to the west in the 1980s as part of the general revival of interest in the art and craft of decorative paper, marbling in particular. Ann Chambers‘s Suminagashi: The Japanese Art of Marbling (1991) and Don Guyot‘s Suminagashi: An Introduction to Japanese Marbling (1988) were, and have remained, valuable resources. Their interpretation of the process was shaped by a number of factors: the type of examples of suminagashi in production at the time, and their background as marblers. Don Guyot, in particular, gave a western Zen flavor to the process. In his view, the artist was the initiator of the action of suminagashi by applying the inks to the surface of the water, but remained passive after that, allowing the inks to spread, be subjected to movement by water and air currents, until the artist decided to apply the paper and obtain the image. These interpretations of the process continue to strongly influence how suminagashi is viewed and taught.

Although there are no early descriptions of how suminagashi papers were made, there are examples of suminagashi patterned paper that can serve as guides and resources for study. The earliest known examples can be found in the poetry collection, the Sanjurokunin Kashu, compiled in 1118. Other examples can be found in museums and collections that can provide a glimpse of how suminagashi was used, and how it evolved over the centuries.

In 1954 Kiyofusa Narita summarized the current status of suminagashi:

“After the Second World War, the demand for artistic papers of quality such as the old suminagashi decreased almost to the vanishing point, but the art still survives. A small quantity of suminagashi is made to order, but it cannot stand comparison with that of days gone by.”

I have been studying suminagashi since the early 1990s – I found Anne Chambers’s book shortly after publication in 1991. However, Narita’s statement has always intrigued me and so I have focused my investigations on earlier examples of suminagashi to gain a better understanding of how these patterns were made, what specific techniques were used.

Although there are no records to give an idea of the number of papers produced at any time in its history, the amount of sumingashi produced, overall, appears to have been limited. Two examples can provide a hint of its rarity: in the family collection of exemplary calligraphy (A Mirror of Gathered Seaweed (Mokagami)) at the Metropolitan Museum in New York, out of 301 specimens, only two contain suminagashi. The Tanzaku (poetry card) collection in the International Research Center for Japanese Studies holds over 900 tanzaku, but only 16 are made on a background of suminagashi. Fortunately, with the growth of the internet, and with many museums establishing digital collections, it has become easier to search out and view some of the old examples of suminagashi. I have included as many as I have been able to locate, so far, in the Gallery, and have arranged them along an approximate timeline to illustrate how suminagashi has changed over the course of 900 years.